27 Oct It All Started With an Ice Cube

How a Chicago architect’s kitchen experiments led to a memorial design for fallen journalists

When architect John Ronan began the design for the Fallen Journalists Memorial, he faced an unusual challenge: how do you create a memorial specifically about journalism? How do you ensure visitors don’t mistake it for a war memorial or a memorial to a specific event, but understand immediately that it honors members of the press who gave their lives?

His answer began in the most unlikely place—with ice cubes.

The Ice Cube Experiments

Ronan’s process started with a simple observation about materials and meaning. “A lot of my work starts with material. And in this case, I thought we should use a transparent material to reference the transparency that the public seeks from journalism. So I started running through the possibilities, which are not infinite.”

Ice seemed like the perfect medium for experimentation—accessible, moldable, and most importantly, not precious. “The ice seemed like a fast way to study things because it’s not a precious material—you can make more in an instant.”

So Ronan did what any dedicated architect would do: he went shopping for ice. “I found some guy who made gourmet ice cubes, bar stuff, and we bought a bunch of bags of ice in an alley in Chicago.”

What happened next would determine the entire memorial’s design philosophy.

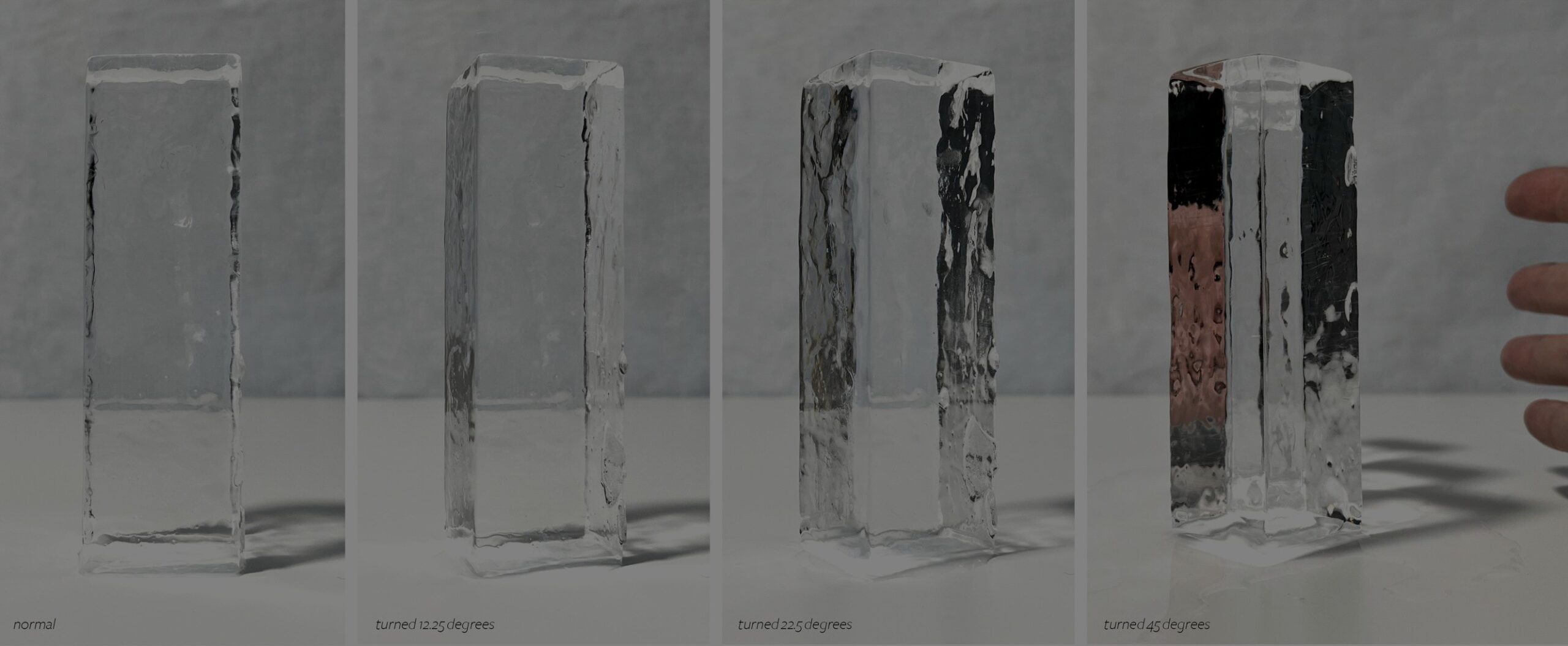

“If you look at the face of an ice cube from straight ahead, it’s transparent,” Ronan explained, walking through his early studies. “But as you rotate it, it becomes shadowy and distorted until it goes opaque. The idea is to build a memorial that’s not purely transparent, but that embodies some of the other things journalists deal with: distortion, opacity, and perspective.”

Material-First Architecture

Ronan’s approach represents what he calls “material-first” architecture, a philosophy that contrasts sharply with conventional design methods.

“It’s the opposite of napkin sketch architecture,” he explained, “in which the genius sketches the form of the building on a napkin and then gives it to someone in the studio, and five years later there’s a building that looks like what’s on that napkin. This is the opposite—it’s more of a journey where you only concern yourself with the next step.”

This bottom-up approach proved especially relevant for a journalism memorial. Just as Ronan starts with material properties and builds outward rather than imposing a predetermined top-down design, journalists start with facts and quotes that organically develop into stories rather than writing backward from a preconceived conclusion.

From Literature, Not Sculpture

Ronan’s influences also set him apart from many architects. “My inspiration draws more from literature than from fine arts,” he said. “I’ve always thought of buildings like a story or a novel.”

This literary sensibility helps explain why the memorial concept resonated so deeply with him. “This project struck a chord with me because I also write and at one point I thought of becoming a writer. I chose architecture instead, but I’ve always loved to write and I’ve always had an affinity for the written word.”

What began as ice cube experiments in a Chicago studio will become cast glass elements weighing more than a ton each, arranged on the National Mall to honor journalists who died pursuing truth.

“I wanted the memorial to be more of an experience to have rather than simply an object to admire,” Ronan said of his vision.

That experience begins with ice cubes and ends with understanding—a fitting tribute to journalists who spent their lives transforming fragments into stories, confusion into clarity, and darkness into light.

Learn more about supporting the memorial at fallenjournalists.org.